Wilderness

11/1/2018 – 2/3/2019

Wilderness

under threat

Fighting for Europe’s last primeval forest – it was with this headline in the Tagesschau of August 3, 2017 that the public learned of the threat to the last remaining section of European wilderness: Białowieża Forest on the border between Poland and Belarus. Danish artist Joachim Koester documented this last intact primeval forest in Europe back in 2001. Exactly 15 years later Białowieża Forest is the site of the ominous meeting of wilderness and civilization – of nature conservation and economic interests. Trees are being felled in the forest at the directive of the Polish government. And the danger persists, despite a 2017 court order of the European Court of Justice to stop logging activities in this nature reserve. At a time when there are barely any untouched regions left on Earth, Białowieża Forest embodies an unresolvable conflict, one that is closely connected to the notion of wilderness: The more humans displace nature with our purportedly civilizing achievements, the stronger the pull that the wilderness exerts on us.

In addition to Joachim Koester, other artists have also explored the topic of “wilderness.” The exhibition at SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT highlighs artistic positions that address various ideas and visions of wilderness. In so doing it puts up for discussion a concept that has in the course of history served as a projection surface for changing counter-images and fantasies of longing beyond the “civilized” world.

Wilderness as lifestyle

The longing for wilderness is once again en vogue and infiltrating civilization. This, at least, is the impression given by the numerous stagings of “untouched” nature in advertising and social media. In many lifestyle trends the desire is evident to enter into direct contact with nature – a paradoxical suggestion.

Wilderness

and reality

The euphoric belief in modern progress shaped thinking at the turn of the 20th century. In a counter-movement, artists began searching for originality, which they believed they found outside bourgeois society. Nonetheless, artistic portrayals of wilderness proved to be constructs onto which ideal images and cultural stereotypes of distant natural landscapes were projected.

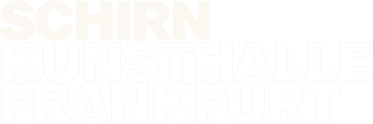

An area devoid of people in the Arctic. The polar bear calmly observes the panorama and the abyss that opens out beneath him. At first glance, it seems as though Briton Rivière has realistically depicted the scene down to the sunset. But he never saw anything like this. Travel journals and visits to London Zoo in Regent’s Park served the artist as source material for his painting “Beyond Man’s Footsteps.” At the same time he makes use of set pieces from a Romantic pictorial tradition, in which nature was portrayed as an overpowering counter-world to civilization.

The impenetrable jungle in Henri Rousseau’s “The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope” shows another notion of wilderness. The hunting scene, which in reality would take place in the open savannah, has been shifted and placed deep within an exotic forest. The two-dimensional, seemingly naïve painting style creates an unrealistic setting, in which the fauna interact with an imaginary flora in the manner of a collage.

Similarly to Rivière, Rousseau did not seek artistic inspiration in faraway lands. Instead he too relied on the popular illustrated press for his themes – and on Paris’ Jardin des Plantes. Untamed nature as a counter-image to an ordered life in a European city assumes dream-like characteristics in his paintings.

Untouched nature

Every major historical research trip had to be documented not only in writing, but also visually. Artists have accompanied scientists on their expeditions since time immemorial, to produce drawings, paintings and later also photographs. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 20th century that artists no longer worked solely in the service of science on expeditions. Indeed, they increasingly embarked on trips themselves.

Thomas Struth’s photographs are a product of his travels. The Brazilian jungle (“Paradise 21, Yuquehy, Brazil, 2001”) takes its place as part of a series of natural landscapes devoid of human life that Struth photographed on all the continents that he visited. Rampant climbers, fans of leaves as well as countless shadow effects and changes in lighting between the trees whisk us away into the mysteries of the forest. Yet this is as far as we can go. The nature in the photo remains untouchable. A melancholy unease arises: In the face of an ever vanishing world “beyond man,” it simultaneously elicits associations of paradise.

Early nature conservation

in the USA

Photographers started exploring untouched natural regions from the mid-19th century onwards. In the United States, their photos became very important, because they changed the political mindset and also rendered a contribution to the preservation of landscapes under threat.

Around 1860 Carleton E. Watkins began photographing the regions of the American West newly opened up by the settlers. He preferred to shoot landscapes devoid of people. This was relatively easy in Yosemite Valley, where American soldiers had driven out the Native Americans living there years before. Watkins’ landscape photographs were breathtaking. They ultimately convinced Abraham Lincoln to designate the area a nature reserve: In 1864, the American President signed the world’s first law of its kind, the “Yosemite Land Grant Bill.” It was the secret hour of birth of the American idea of national parks, which the federal authorities were to officially implement in Yellowstone in 1872.

A change of opinion in the public awareness was also decisive in this context. Indeed, for the first European settlers the horrors and dangers of the wilderness morphed into the idea of a nature worth protecting in view of advancing urbanization and industrialization.

Mountain landscape

as illusion

In his works Julian Charrière addresses the ambivalence of nature and culture. He pursues the question as to which artistic means can be used to trace the overlaps and contradictions between pictorial reality and the reality of our lives.

A native of Switzerland, Charriére centers his “Panorama” series on a symbol of cultural identity. Snow-covered peaks rise up out of misty valleys in the manner of Romantic paintings. Yet on closer inspection the observer is brought back to harsh reality, for in actual fact the artist created the majestic mountain landscapes from piles of soil and flour on a construction site in Berlin, which he then photographed. In this way Charrière questions not only our perception, but also our idea of natural landscapes, which we are often all too quick to label idyllic.

Wilderness as experience

Artists repeatedly explore wilderness as a place that is unpredictable and that changes aesthetic perception. Untouched nature itself has frequently been a permanent site of artistic activity outside the established art centers.

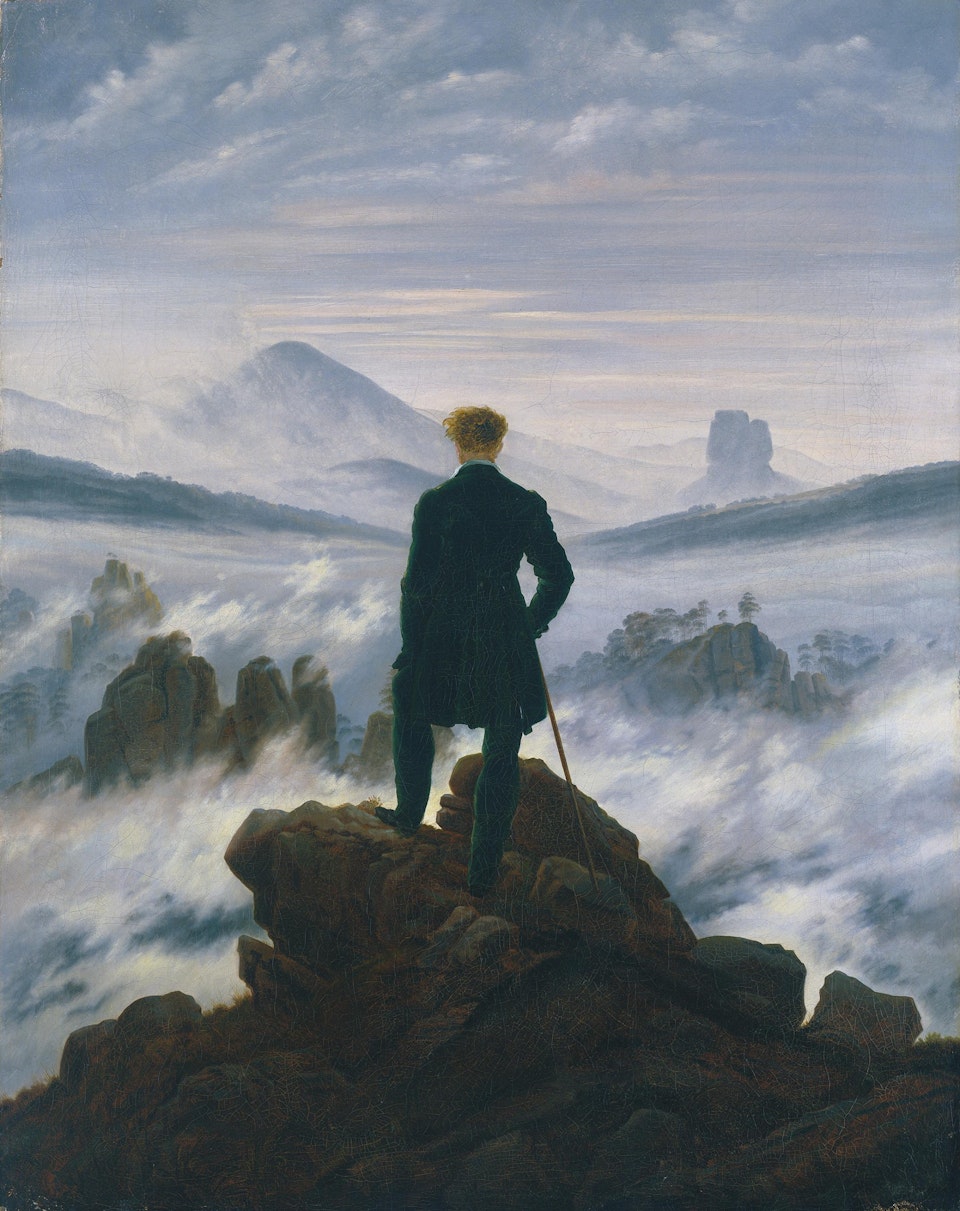

The paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe are filled with the belief in the power and intransience of nature. Her daily experiences of Texas’ broad plains at sunset inspired the artist to create “From the Plains II.” O’Keeffe succeeds in capturing the impressive expanse of this barren landscape and the dramatic spectacle of light in form and color. Here, the Texan desert becomes a realm of sensory experience. The abstract shapes and the use of the unblended colors red, yellow and orange serve purposes of accentuation and transformation. The malleable and the shapeless, the tangible and intangible flow harmoniously into one another.

“My first memory

is of the brightness of light

– light all around.”Georgia O’Keeffe, 1976

Experimental

set-ups

Ever since the 1960s, Land-Art protagonist Richard Long has been staging his artistic interventions in the expanses of nature.

Walks lasting days and weeks are part and parcel of Richard Long’s artistic practice. He explores inhospitable landscapes, with no infrastructure and no trace of civilization. It is at these places that Long composes linear, spiral, cross-shaped, elliptical or circular shapes and contrasts wild nature with precise arrangements, which he subsequently photographs. In this process, he uses the movement of his own body in the landscape and the time required for this as a scale for his transient art.

“My work is real,

not imaginary or purely

intellectual.

I work with

the world as

I find it.”Richard Long

A new

cultural

dimension

Their skepticism of the Western enslavement to progress led artists to experiment with alternative aesthetic experiences in the 1960s and 1970s. This went hand in hand with a curiosity about and desire to immerse themselves in the spirituality and close connection to nature of so-called primitive cultures.

Ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss coined the term “wild thinking” in 1962. He used it to describe the mindsets of archaic cultures whose members live in harmony with nature and whose outlooks were shaped by holistic and mythical worldviews. “Wild thinking,” as a counter-concept to the objective scientific orientation of the West, strongly influenced the new manner of addressing non-European cultures in the art of this period.

The works of Ana Mendieta are infused with the spirit of “wild thinking,” which views the systems of order practiced by indigenous peoples as equal to those of Western societies. Mendieta places living creatures and natural phenomena in a magical relationship, the way she herself witnessed the religious cults of her native Cuba.

Ana Mendieta reverses the separation of man and nature uwing her own body – which forms a symbiotic connection with the landscape. The photo, taken in Iowa (USA), also alludes to the Cuban exile’s attempt to overcome the feeling of her cultural uprooting.

“I become an extension

of nature and

nature becomes

an extension of my

body.”Ana Mendieta

Wilderness and man

The thicket of rampant leaves appears impenetrable. A green bird-man combs through the dense jungle. Is he following his desire, namely the woman amid the greenery?

One of the major interests of Max Ernst and his fellow Surrealists was to explore the unknown and innermost depths of the human soul. Influenced by the still young discipline of psychoanalysis, as of the 1920s they focused on examining human instincts. They wanted to re-expose the desires suppressed by civilization and convention, i.e. people’s “inner wildness.” To this end they explored their own dreams and memories using creative techniques such as “automatic writing,” hypnosis and trance. Max Ernst’s dark avian creature could symbolize the artist himself, and the thicket his psyche – the naked woman cowering at the right-hand edge of the picture arouses his desire, and he sets out to reach her.

“I paint like an ape.

The ape phase

is in all

my work.”Karel Appel, 1990

The

primitive

in painting

Wild brushstrokes and garish colors impulsively form a human figure. It appears as animalistic and fleeting as the painting style used to create it.

Karel Appel’s apparitional figure refuses to be clearly interpreted. On the one hand the “Wild Boy” seems naïve and childlike; on the other it exudes a certain aggression. It remains unclear who he is and where he comes from. His coarse features, like the unblended colors, have associations with artistic forms of expression used by primitive societies. Yet his stylized uniform is also reminiscent of schoolchildren, whom Appel encountered in Germany.

Appel was a member of the CoBrA group. Among the things its members called for in their artistic manifestos was a reappraisal of the crimes of World War II committed against other peoples in the name of Western civilization. With this piece created in 1953 Appel questions the customary boundaries in our worldview between “culture” and “barbarism.”

Wilderness

in cities

Artificial wilderness

A creature makes its way through a virtual wilderness. It responds to certain outside influences as though externally controlled. Is this an intelligent creature? Does it have an identity of its own? Does it have an awareness?

There is something strange and disconcerting about the faceless being in Ian Cheng’s simulation “Something Thinking of You,” because we cannot categorize it. In real time it roams around a virtual ecosystem devoid of humans and animals. This world, in which the boundary between nature, man, animal and technology has seemingly dissolved, has post-apocalyptic qualities. The creature makes decisions based on fundamental emotions such as boredom, the urge to play, the need for rest, or hunger, as well as external influences like the season, climate or its immediate environment. The observer cannot predict its next steps – and neither can the artist. The simulation is programmed such that it continues to write itself. Ian Cheng created these fantasy worlds to demonstrate that artificial intelligence can indeed act without humans in the age of the Anthropocene.

Deceptively

real

Found artifacts from the throwaway society blossom anew as floral forms. Joan Fontcuberta arranges items found on the wayside of industrial areas and trash into exotic constructions, making them look like real plants.

Thanks to their scientific staging, the fictitious plants become credible reality. They appear familiar and yet mysterious. The artist calls them “pseudoplants.” He photographs them strictly in black and white, as though he were a botanist proceeding formally like a scientist. He gives each plant a Latin name relating to its components. The exotic plants are an ironic commentary on the age of genetic engineering and environmental pollution, for without human intervention in nature they would not exist.

Into the wilderness!

Having been on this short journey of discovery you are now well equipped to explore SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT. The extensive thematic exhibition illuminates and questions our sustained fascination for the concept of wilderness, which defies all attempts to capture it in an artwork or exhibition. Discover paintings, drawings, photographs, video works, sculptures and installations by around 30 artists from 1900 to the present day.

Insider Tip

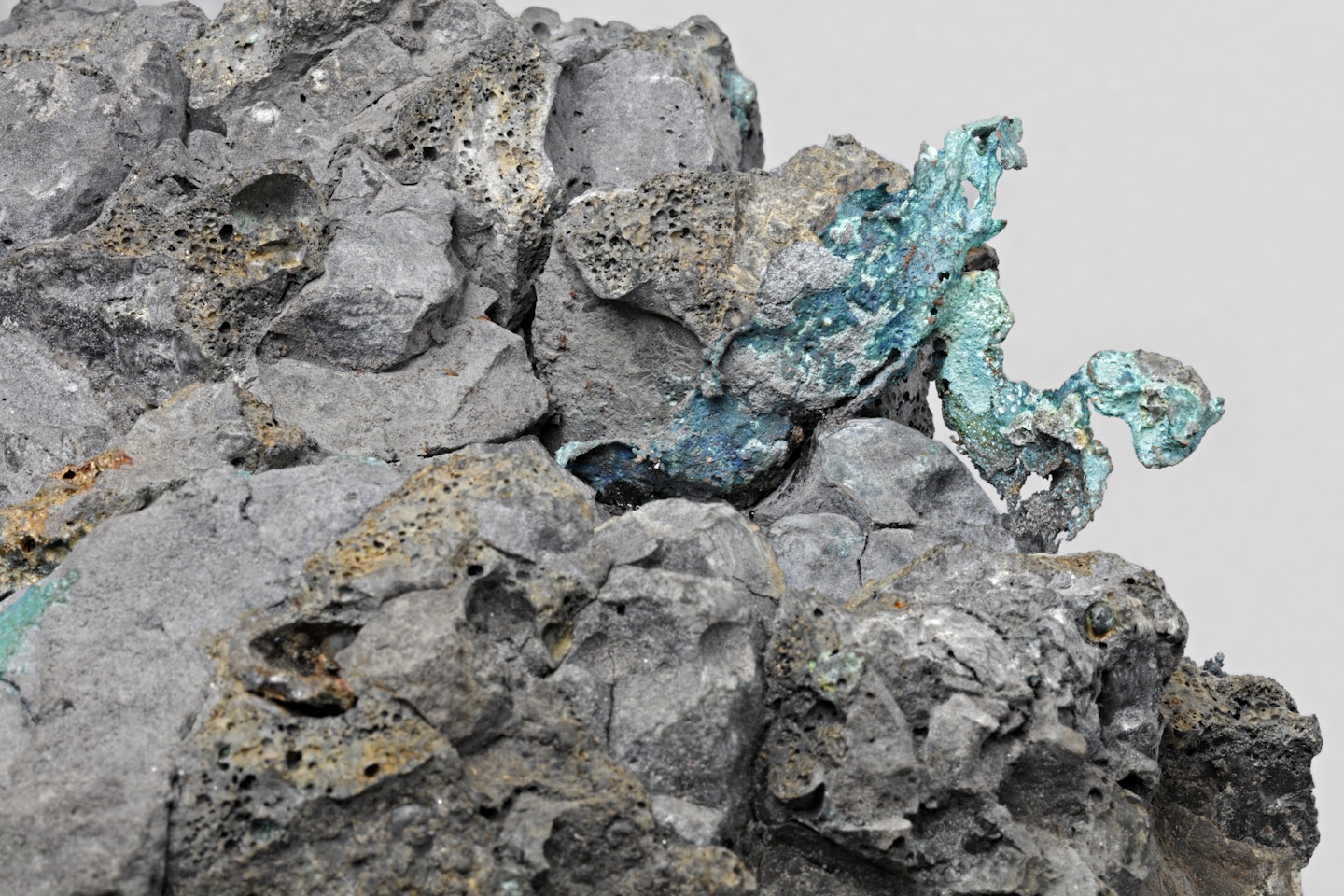

Art or

alchemy?

The works of Hicham Berrada are located on the border between art and science. “Ghost #1” resembles a seething landscape in which everything is moving and reforming. The artist acts like a painter, using chemical elements to create “living artworks” outside the lab. The seemingly alchemical vividness evokes associations on the one hand of the origin of nature “before man,” and on the other of post-apocalyptic visions of a world “after man.”